Nem Nem Soha

Hungary’s Balancing Act: Brussels, Moscow, Beijing and Washington.

Otium Den recap:

South by Southwest on the Danube

Last week was a welcome change from Singapore’s year-round humidity for a few days of autumnal sunshine in Budapest. The Brain Bar festival puts its faith in meteorology each September to host in City Park, just off Heroes’ Square. Blue skies ensured several thousand attendees never had to retreat inside.

Brain Bar has been called South by Southwest on the Danube. It features art and technology, such as Neil Mendoza’s Spambots; music, including Hungarian folk dancers and a local beatboxer; and debates, with a small tribute to Charlie Kirk in the form of a ‘change my mind’ stand. Speakers are the main attraction. Hungary’s rightward turn under 15 years of Viktor Orban means their themes are often contrarian. But it’s not an echo chamber. Left-wing economist Mariana Mazzucato sits alongside Peter Thiel and Jordan Peterson in the event’s impressive alumni.

Around half of the crowd are high school and university students. Their obvious curiosity and enthusiasm are a welcome antidote to the idea Gen Z only want content in 10-second TikTok format. Because the sort of teenager that wants to attend Brain Bar is likely quite bright, the festival also serves as a talent market. International companies like SAP and KPMG exhibit alongside the army’s Hussars unit.

The Future of Europe

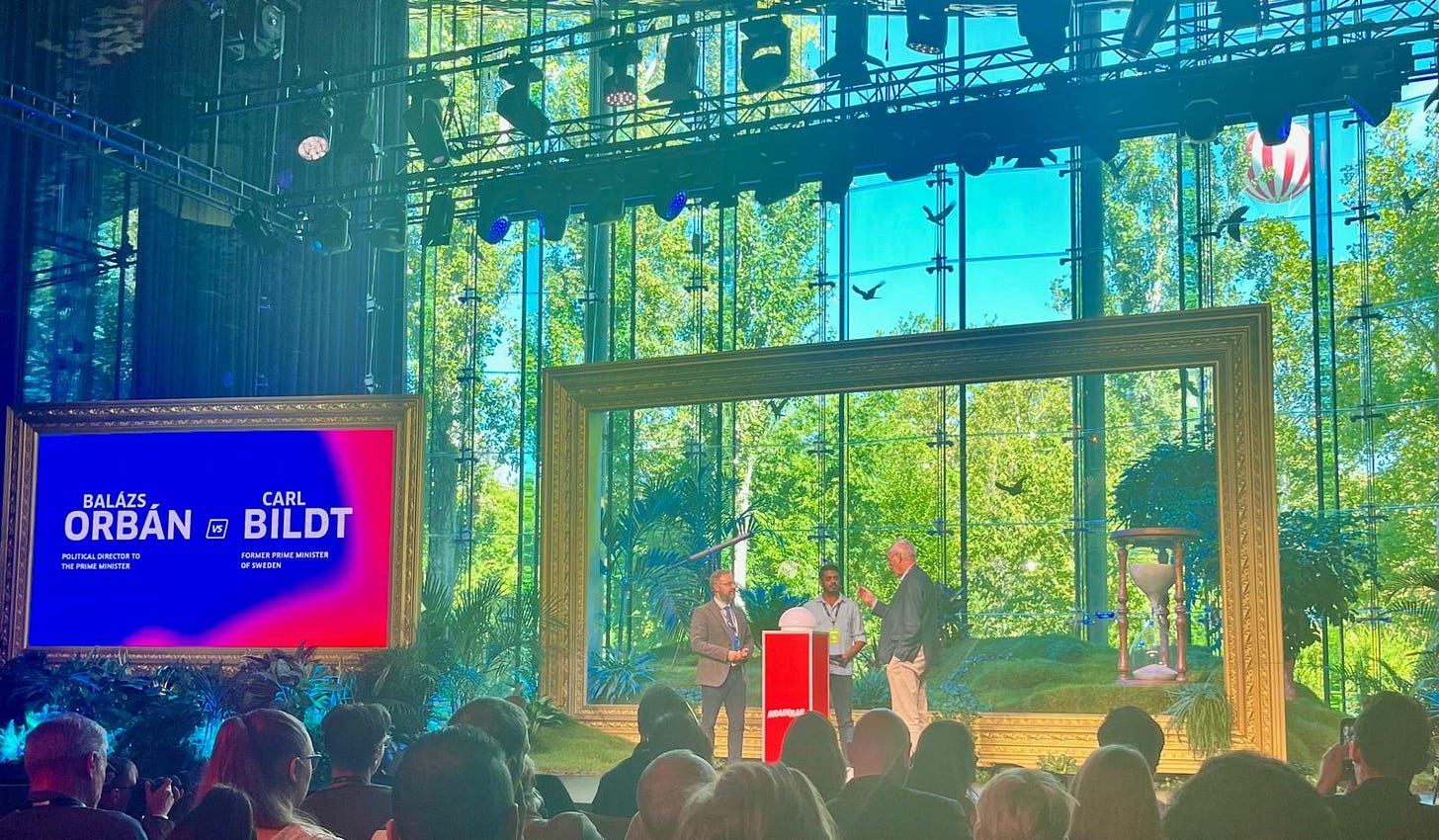

The big main-stage debate was between Viktor Orban’s political director Balazs Orban (no relation) and former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt. Orban was pugnacious, arguing the EU thwarts Hungary’s autonomy. The 2015 refugee crisis still lingered as a sore point, when Angela Merkel’s hospitality meant hundreds of thousands transiting through Hungary to reach Germany. Viktor Orban responded by building a fence along its Serbian border and labelling Hungary a “zero-immigration” regime. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) later ruled that Hungary had breached EU law and has since withheld billions in funds. In both Orbans’ eyes, Hungary was the victim of EU imperialism.

Balazs believes this moral grandstanding continues today in EU economic policies. He criticised tariffs on China’s electric vehicles and its response to Trump’s trade renegotiations, calling it needlessly antagonistic. He also represented Hungary’s growing Russiaphilia, telling Bildt that the EU “only talks about war and ideological confrontation”. He framed his position to appeal to the young audience. Hungary wants this demographic to be prosperous. That means good relationships with the two superpowers leading the AI revolution and cheap energy from Russia.

But Balazs didn’t have it all his own way. Although the live poll showed a win for the motion that the EU’s relevance is declining, Bildt landed some good punches. The biggest cheer came when he interrupted Balazs’ rant to point out that the freezing of EU funds was as much about corruption as immigration policy. The EU alleges that Orban’s government channelled development funds to allies and family members. That resonated, and speaking to local businesspeople later, I heard a lot of discontent about the increasing prevalence of crony capitalism. Budapest itself has successively defied the dominance of Orban’s Fidesz coalition, electing an opposition mayor for a second term last month.

Singapore and Hungary

My contribution to Brain Bar was as part of a session on Singapore: A Superpower from Scratch. What can countries like Hungary learn from the Singapore model? It’s already imbibing the lesson in keeping one party in power for a long time. Managing geopolitical sensitives is another thing it wants to replicate.

Hungary’s foreign policy is very nuanced. Orban is a darling of the MAGA movement for his anti-globalism and cultural conservatism. Yet Hungary is also China’s closest partner in the EU. Orban is one of Benjamin Netanyahu’s oldest friends and Israel’s most steadfast ally in Europe. Hungary recently withdrew from the International Criminal Court (ICC) after the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Israel’s Prime Minister. But Hungary is also a great friend to Israel’s fervent critic Turkey, supporting its EU accession and bolstering trading ties. Partly a nod to Hungarians’ Turkic ethnic heritage but also a symbol of its pragmatism.

I asked Singaporean investor Hian Goh (Hian Goh /Unreasonable Mindset) how Singapore managed a similarly realist stance. China is the city state’s largest trading partner, but Singapore also maintains very warm relations with the US. Goh said exercising such neutrality required leverage. Singapore has assets, running budget surpluses and able to draw upon over a trillion dollars in sovereign wealth funds. So, China cannot buy influence through its Belt & Road initiative, which creates debt burdens through its infrastructure financing. America, meanwhile, gets access to Singapore’s Changi Naval Base. It’s a vital platform in one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. These assets stop Singapore becoming beholden to either power or being bullied into picking sides.

Imperial pawn?

I read Norman Stone’s Hungary: A Short History on the flight over to Budapest. The late British historian spent his final years in Hungary as an advisor to Viktor Orban. It’s a sympathetic account of the Central European nation and contextualises why Hungary assertively pursues autonomy. Once a dominant Middle Ages kingdom under Janos Hunyaldi, its more recent history is that of an imperial pawn. Hungary became part of the Habsburg Empire after the end of Ottoman rule in 1718. Its independence was finally re-asserted in 1848 under first Prime Minister Count Lajos Batthyány. His appointment and modernisation program was approved by the Austrian Emperor. But Vienna then performed a volte face and rolled things back, eventually executing Batthyány just a year later. Batthyány's sanctuary lamp stands next to parliament as a memory of this betrayal.

In the 20th century, Hungary remembers both wars as ones they were dragged into by its surrounding sphere of influence. After defeat in the first, the Treaty of Trianon took away two thirds of Hungary’s land and left millions of ethnic Hungarians in modern-day Romania and Slovakia. Her population was reduced from 20 to eight million. Stone argues Hungary was treated uniquely harshly amongst the defeated powers and Nem Nem Soha (No, No, Never) remains etched in the national psyche in response.

In 1945, Budapest was the site of the Nazis’ last stand, as the Germans and Hungary’s compliant Arrow Cross regime tried to delay the Soviet advance on Vienna. The Red Army lost 80,000 men in what the Soviets saw as an unnecessary siege in a war that the Axis powers had already lost. That engendered Soviet bitterness that often saw Hungary treated worse than other satellite states during the subsequent Cold War.

I know far too little to judge whether Hungary can rightly paint itself as a victim of circumstances. But that history helps explain why Orban’s schtick has largely proved popular. Ideological alliances haven’t served Hungary well and bloody-minded independence looks a better bet. But that assumes today’s new empires want to deal with Hungary on purely transactional terms; that they won’t try to manipulate it into new spheres of influence. Politico reports that Trump is now helping Brussels put pressure on Hungary over its continued import of Russian gas. Soon, Orban may have to choose between East and West.

Law of Scale

The closing speaker at Brain Bar was the British physicist, Geoffrey West. His law of scale asserts that mathematical regularities mean properties scale in predictable ways. West is famous for applying this to cities. But it’s applicable to nations too. Hungary cannot benefit from the same super linear scaling as the world’s superpowers or supranational bodies. Its leverage is inherently limited, and it is fated to fall into the gravitational pull of larger powers.

It can assert itself by winning influence and resisting the EU as part of a larger bloc. (Bildt conceded that Balzas Orban was right about the destructiveness of some of the EU’s policies.) But there’s a balance to be struck between pusillanimity and recklessness. Singapore is prudent in deciding between assertion and retreat. It was taken aback when hit by new US tariffs but didn’t retaliate.

A wise British Prime Minister once said he was pro cake and pro eating it. But it was a cake that eventually brought him down. If Orban is to avoid the same fate, pragmatism might mean picking sides.