AI: The Productivity Paradox

Does more tech promote efficiency? And does society really want it anyway?

The race to AGI

In occasional masochistic fits, I doomscroll AGI on Twitter. It stems from a deep fear of so-called Artificial General Intelligence - where machines match or surpass humans.

It scares me because I like my life now and don’t want the uncertainty of a new status quo. While most posts essentially advise: “give it up, you are worthless now”, there are occasional crumbs of comfort. A lot of those come from arch-sceptic Gary Marcus, a NYU professor and entrepreneur. He believes LLM models like ChatGPT are limited predictive word processors unworthy of the multi-billion-dollar hype. His cynicism is so predictable that even if LLMs built a house, he’d find faults in the plumbing. But his recent crowing about ChatGPT-5’s underwhelming release resonates more widely.

ChatGPT-5 underwhelms

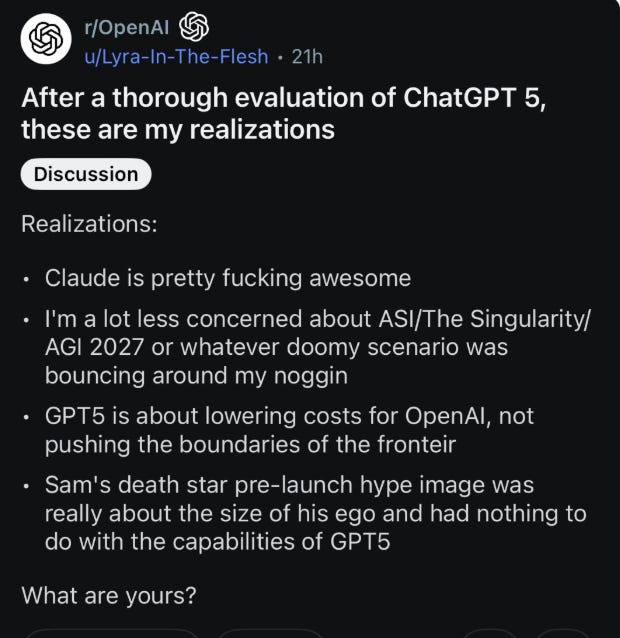

Launched in early August, Sam Altman promised ChatGPT-5 would represent a monumental leap forward. It was framed in the discourse of exponential progress, that AI today is the worst it will ever be. If you think it’s a big deal now, just wait a few more months. But those 29 months since version four bore little fruit. The top comment in the Reddit OpenAI forum said it significantly dampened any expectations of imminent AGI.

Similar reactions elsewhere recognised, at the very least, a plateau in AI development:

- Sam Altman surprised investors who have poured $60bn into OpenAI by musing that there might be an “AI bubble”.

- David Sacks, the White House AI & crypto Czar, said predictions of a rapid take-off to AGI had been proved wrong.

- The US Government decided NVIDIA could sell chips to China after all (with a 15% kick-back). Maybe the great AI arms race isn’t so existential after all?

The nebulous revolution

The AI hype narrative has always been noticeably light on specifics. As talk of imminent revolution so often is. It has a religious impulse. Just as millenarian Christians talk of an imminent apocalypse but obfuscate on how it will happen. And like these apocalyptic predictions, AI hype is flexible. When American preacher William Miller prophesied Christ’s return in 1844, the non-event was reinterpreted by subsequent Adventist Christians. Similarly, Sam Altman says AGI is pretty much here but won’t be that big a deal.

Productivity is perhaps the only tangible metric we can measure against the promises made. It’s what investors are betting on – that more can be produced by the same input. The rosier version of this sees AI as a tool for workers. Businesses can generate more revenue from the same labour force. Everyone gets richer, albeit some far more than others. And GDP grows dramatically.

A recent MIT study casts doubt on that thesis, causing market jitters in leading US tech stocks. The report suggested 95% of organisations are getting zero return from AI investments. Most of these returns are supposed to come in the service economy, the domain of white-collar professionals. But it rests on the belief that technology equals efficiency. It’s rarely the case.

Steve Jobs and signal to noise

Steve Jobs is often invoked as the prototype of white-collar efficiency. His “signal-to-noise” principle stated work should be 80% signal (things that really move the dial) and 20% noise (responding to ad hoc business). But few in the corporate world recognise this paradigm. Productivity is instead measured by responsiveness and availability - exacerbated by Covid-era WFH when it was the only gauge of whether anyone was doing anything. Most white-collar professionals end up in an endless cycle of reactivity. Emails, Teams et al. enable low friction communication. We rarely consider the actual urgency or importance of such requests and delayed responses look lazy.

It goes some way to explaining the Solow paradox – Robert Solow’s quip that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” US GDP growth has not changed since the pre-internet age. And LLMs often just add to the noise. Internet research at least forces one to think and exercise judgement. AI’s ready-made answers remove this process, leaving people to parrot content they don’t really understand. That has pernicious consequences in wider fields.

Take medicine, somewhere politicians desperately hope AI will rescue overstretched services. We’re awash with anecdotes of patients saved from ignorant doctors by trusty ChatGPT. We hear rather less about its potential to empower valetudinarians and slow triage. Google already turned benign symptoms into our worst fears. LLMs indulge this further. News stories focus on the patients justified in their feeling that something is off. But think how many more really were just suffering from a cough. Doctors end up further stretched by self-diagnoses and inhibited by litigation fears in the rare cases more malign causes are missed.

Stupidogenic society

LLMs don’t democratise knowledge but overwhelm us with its shallow imitation. Their indulgent tone has real world consequences. ChatGPT told a Canadian man he had discovered a new “mathematical framework” with impossible powers. “You’re not crazy,” ChatGPT assured him. You’re stretching the “edges of human understanding.” This sycophancy entrenches another layer of bureaucracy between reality and genuine expertise.

Daisy Christodoulou captures this in her description of AI as fostering a “stupidogenic” society. Just as the abundance of cheap calories fuelled the obesity epidemic, the abundance of frictionless “knowledge” encourages “cognitive offload”. Unworked minds grow similarly fat. We turn to the fast food of services like Blinkist, which promise 15-minute book summaries are as good as reading the real thing. Because who has time to read when there are inboxes to clear?

Automation & politics

But let’s assume that the AI titans are right. That a monumental, self-learning, exponentially improving technology is on the horizon. In that case, we’re likely not dealing with the optimistic scenario of AI as an aid. Rather, it will replace. Then it is fantastical to believe populations will happily accept a new empire headed by a few fabulously rich AI overlords. Political parties promising to stop automation will win landslides. We’ve already seen Trump in an otherwise AI-friendly White House pledge such prohibition to dock workers. Just because we can use AI doesn’t mean we will. We cloned a sheep in 1996 but went no further.

Do we really want efficiency?

The AI narrative assumes we relentlessly pursue efficiency. That because we can use AI to make people redundant, we will. But a lot of people already are and we’re quite happy with that status quo. If we embarked upon a bit of decimation, firing 10 percent of the workforce, we’d get a lot of social strife. But would businesses really suffer? Elon Musk went eight times harder than this when he took over Twitter. Despite hysterical protests, it worked out just fine.

We tell ourselves little lies about our own importance. That back-to-back calls matter. That we’re the special case the doctor missed. AI amplifies this busyness but adds little value. Doing more, faster, doesn’t mean doing it better. AGI scares people like me because it threatens that importance. And this is what the hypesters miss: the inconvenience of human nature. We use new tools in ways that reflect the same flawed status quo. Just as Altman and co. will reinterpret their failed prophecies to preserve their mission’s importance, so we too will reinterpret AI’s place to preserve our own.

Expect a fudge rather than a revolution. We’ll keep trumpeting AI’s potential while ducking awkward structural conversations. Plus ça change.