Is Democracy Decadent?

Does Vox Populi really guarantee prosperity?

Otium Den recap:

I’m having my best season ever in Fantasy Premier League. I’ve improved on my usual two millionth place finish and sit in the top 55,000 of the 12 million plus people who play the game.

It involves picking Premier League footballers within a given budget and earning points for their performances. In previous seasons, I’ve avidly read and listened to the vast resources available to inform one’s selection. It’s been a poor return on investment. This season’s success has come from a different approach – blocking out that noise and sticking with a few conviction picks through leaner weeks.

What does this have to do with democracy?

I think about it as I read Matthew Syed’s rousing defence of it in The Times. Syed points to global polls that ask people where they would live if the world truly was their oyster. Liberal democracies, in the form of the biggest Western powers, always come out on top. These revealed preferences, Syed argues, prove we should all be a little more positive about a system he calls a “belter”.

I’m a big fan of Syed. And his article is timely, as figures on the left idealise Nicolás Maduro’s rule and ones on the right suggest Adolf Hitler was actually a “cool” guy.

But Syed’s democratic cheerleading risks complacency — the belief that all will be OK if we bask in the glow of morally superior government. It ignores its inherent flaws. Chiefly that you can win votes by people-pleasing and changing policies on a whim, rather than through delivering results.

Democracy ≠ Prosperity

The countries everyone wants to live in are also the richest, and democracy is not always a prerequisite of that wealth. I don’t see an obvious correlation in Asia where the so-called Asian Tigers - South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore - are far wealthier than most of their neighbours. The former two achieved rapid economic growth before democratic transitions in the 1980s and 90s. Hong Kong was not a democracy under British rule (and even less so back in Chinese hands). Meanwhile my home of Singapore blends elections with more authoritarian practices.

The city state only gets a fleeting mention in Syed’s article. It’s an uncomfortable fit with his thesis that “economic success and democratic institutions are indivisible”. Singapore lacks a free press, is accused of gerrymandering, and its founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was hardly effusive about democracy’s benefits. Lee believed it produced “erratic” results as fickle electorates “vote for a change for change’s sake.”

Lee thought that such arbitrariness threatens economic development. Singapore’s sovereign wealth funds are a good example because they require the discipline of delayed gratification that free elections can thwart. Today its total combined assets are estimated to be US$1.7 trillion. Building that was painful. It meant imposing high compulsory savings on workers, restricted welfare and no immediate dividends. The result is that investment returns now fund about 20 percent of government spending, instead of high taxes or borrowing. That long-term planning would have been jeopardised by a realistic opposition party campaigning to use this money for a welfare splurge.

“It’s all fake”

It’s quixotic to believe democracy always yields prosperity, and that anything else collapses into kleptocracy. Of course, authoritarian rule risks caprice in the form of “strongmen” without accountability. But so does democracy when governing descends into signalling. Speaking on the Spectator podcast, Dominic Cummings refers to ministers making grandiose statements about issues they only just found out about. “It’s all fake”, says Cummings. Politicians just try and say the right thing, rather than doing anything.

It’s why a recent Adam Smith Institute poll suggests 33 percent of British 18-30 year olds would prefer an authoritarian system, led by a decisive figure. Someone who actually exhibits some obstinacy, rather than endless reactivity. More cheeringly, there is evidence the electorate responds well to figures who show steel. A slightly trivial example perhaps, but I think of Kemi Badenoch’s response to the TV series Adolescence last year. In the midst of media fury that she had not bothered to watch it, she calmly stated her belief that policy should not be dictated by fictional drama.

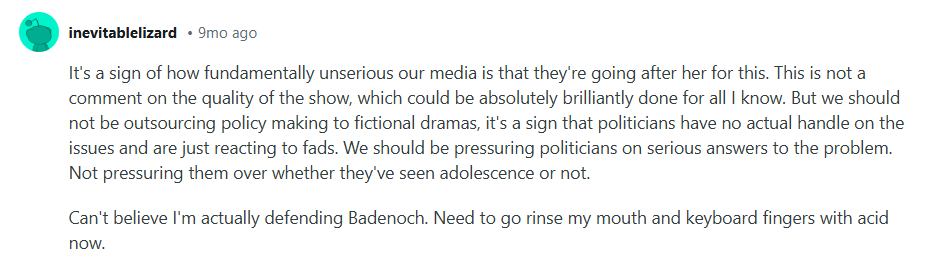

The Reddit thread, Kemi Badenoch is right about Adolescence, shows a receptiveness to her response. Commenter inevitablelizard says, “We should be pressuring politicians on serious answers”, not “whether they’ve seen adolescence or not.” Interesting too because inevitablelizard is not a Badenoch fan. The redditor promises to wash his or her mouth out with acid for defending the opposition leader.

Followership or Leadership

It’s an example of leadership over “followership”. Lord Wolfson and Baroness Shawcross-Wolfson use the latter term in the Policy Exchange’s Future of the Right paper to describe parties’ “habit of asking the public what they want to hear and trying to provide it.” Mirroring public sentiment rather than shaping it is short-termist and futile.

Parties are far too in thrall to the temporary nature of polls that gauge those public attitudes. They don’t share my Fantasy Premier League patience or Singapore’s investing mantra. Both involve weathering short-term discomfort rather than changing approaches day-to-day.

Yes, that rests upon having some good ideas in the first place. And not sticking with them pigheadedly if the facts change. But it’s a conviction first approach. In the political sphere, this means convincing the electorate of what you believe is right, not what they want to hear.

Democracy works when it removes tired governments and sparks new ideas, like Thatcher’s smashing of the post-war statist consensus. But we do democracy a disservice if we kid ourselves that the ballot box guarantees prosperity and ignore the successes of less liberal regimes. Chasing every headline and poll just means embracing the same inconsistency we criticise in kleptocracies.

British democracy may not grant the same patience as Singapore’s hybrid system. But that doesn’t mean resorting to myopia. Conviction can bear fruit. Let’s see a little more of it if we want a proper defence of why democracy works.